|

[ lisez cet article en français ]

The GREAT

STORY of FILM MUSIC The GREAT

STORY of FILM MUSIC

les Inrockuptibles

By Christophe Conte

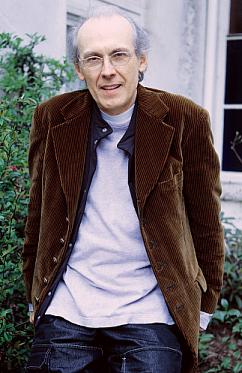

photograph: Renaud Monfourny

During the last 40 years of the musical color chart, Michel Colombier has almost never left the

gray: man of the shade, the "éminence grise", the power behind the throne; but never colorless.

The Flight of Colombier

Exiled in Hollywood for more than twenty years, Michel Colombier is a discreet man whose name has

often been effaced behind the ones of Gainsbourg, Pierre Henry or Prince. But from Melville to

Demy, this chameleon has written some of the most remarkable music ever for the big screen.

Michel Colombier shows all the external signs of an American in Paris. He arrives dressed in a

rather curious combination of elegant sportswear (pants with many pockets, almost baggy) and

strict bourgeois uniform (cashmere overcoat, tailored jacket), bringing forward the slender

silhouette of a person of distinction and a smile full of perfectly aligned teeth. We almost did

not recognize him, we had kept an image leftover from record covers from the 70's: that of some

sort of disheveled Zebulon, bearded and pale, having spent too many nights in the studio, with

spectacles large enough to be confused with a Harley Davidson's side-view mirror. Today he looks

like an English lord, showing his age of 60 as if he were 50. An American in Paris all the way:

his wife and children are shopping in St Germain-des-Prés while he gives interviews at the café

(de Flore, of course).

One must say that Michel Colombier, in spite of a deeply rooted French name, is almost American

and practically not Parisian anymore. He has been living and working in Los Angeles for almost

thirty years, in the heart of the film industry, at the fringes of the record industry, always

servicing one and at the bedside of the other, seldom with himself. During the last 40 years of

the music color chart, Michel Colombier has almost never left the gray: man of the shade, the "éminence

grise", the power behind the throne; but never colorless. "I am comfortable being in the shadow",

says he without any frustration, "I have never missed the lack of notoriety. No one ever knew

that I wrote the music for Antenne 2's opening and closing titles (with Folon's animated

blue men) or the one for Salut les copains. I started as the ghost writer for Michel

Magne, I grew up like this. My father had very strict principles, he was a purist, he used to

remind me that an artist is serving the art and not the other way around." His ego equals zero

on the vanity scale, but his interior wealth is probably worth more than all the adulterated

praises. Do we know that Colombier wrote the score of Purple Rain while the rain

of superlatives were only showered toward Prince? Do we know that, more recently, he was the

other Frenchman working for Madonna while his name never made it to the lips of the cow-girl?

Experienced in being eclipsed, Colombier has only raised his voice once, in 1967, when the first

release of "Messe pour le temps présent" was distributed in the stores without mention of

his name, crediting only Pierre Henry. The sleeves were reprinted, but thirty years later, one

still only hears of the clever grand father of "musique concrete" forgetting that what really

titillates the DJ's, the ad agencies and the dancers of the techno-planet, are the disturbing

jerks unpinned by Colombier and his uncontrollable grooves. Colombier diplomatically states: "my

music alone would have never interested the public, it was, in that case, a fusion. Pierre's

edits and sound effects have brought a formidable touch, invaluable".

In the cinema, especially when associated with Gainsbourg (eight times between 1967-70), the name

of Colombier goes by like a shooting star during the main titles. One can barely see him behind

the "man-with-the-cabbage-head" (Gainsbourg, l'homme à la tête de chou). Nevertheless he's the

one orchestrating such wonders as "Manon" (from "Manon 70") and of course "Requiem pour un

con" (from the "Pacha"), corner stones that will lead Gainsbourg all the way to "Melody

Nelson". The influence of Requiem pour un con's break beat radiated internationally from pop to

hip-hop. It was one of the visionary strokes of genius that Colombier scattered throughout his

productions in those days. It is him again who draws the fugitive lines (Sous le soleil

exactement) and blows the pop bubbles (Roller girl) of the musical comedy Anna.

At the end of the 60's, Colombier tries his luck for the first time in the U.S. He went to

compose and arrange Petula Clark's TV special, he got his first commissions for both the little

and the big screen and, thanks to Herb Alpert, the vivacious leader of the Tijuana Brass and

owner of the label A&M, Colombier ends up creating an ambitious solo album which became mythical:

'Wings', in 1971.

The most stunning film scores written by Colombier, during his great period 1970-75, are the

ones created for French films nourished by the imaginary of American detective novels ("Un

Flic" by Melville) or simply by the mythology of the "Yankee's way of life" ("L'Héritier"

and "L'Alpagueur" by Labro). With Melville (who died too soon and left orphan this

prodigious union), Colombier weaves a theme for piano, oboe and large orchestra which will remain

as a final statement of lone melancholy in the history of film music. With Labro, who took

himself for Melville without ever coming close, he invents effective structures, tense and

aggressive, held up by rock dynamics, not unlike Lalo Schifrin and Morricone at the same period

("Sans mobile apparent"). The other big endeavor of Colombier, before his final flight toward

the "New World", is "Une Chambre en Ville", by Jacques Demy. We know that Michel Legrand,

usual composer of the enchanted man from Nantes, had declined to associate himself with this

crazy project of a musical over social injustice and fractured human relationships. A musical

tragedy, in fact, which was a nightmare for Demy (ten years of rejections, interruptions,

throwing in the towel and casting upheavals) but whom Colombier accompanied loyally until the

birth of the film in 1982. The film is an impossible challenge, especially for the composer, who

comes after Legrand with the mission to take the opposite course of "Les Parapluies de Cherbourg"

(the Umbrellas of Cherbourg), "Les Demoiselles de Rochefort" or "Peau d'âne". The score of "Une

Chambre en ville" stoned from the flamboyant charm of the tandem Legrand/Demy, is an

ungrateful exercise which nonetheless ended in a master piece that evokes more Brecht than the

American musicals. "My father was a pit musician in an opera house and I have been exposed, very

early in life, to all sorts of stage works, I have been molded by all that. I was familiar with

the language of tragedy. 'Une Chambre en ville' has been a film totally misunderstood,

the potential public thought that it was only about strikes, there was a major miscommunication.

Simultaneously, there has been a very touching support of the film by film makers, intellectuals

and film critics, there was even mention of how deep my music was".

The call from Hollywood became natural for a musician who had never accepted the sort of disdain

that is usually associated to film music in France. "In France, often the composer is not paid,

only associated to the risky prospect of profits. If the film is a flop, you have wasted months

of your life. In the U.S., the composer receives usually a decent compensation at the time of

the writing and receives an adequate music budget. Since I'm easy going and also a perfect

chameleon, I absorb like a sponge; it has been very easy for me to adapt to Hollywood's style of

working, this is why I had no problem whatsoever in the U.S.".

Since the 80's, Michel Colombier has written over fifty film scores, often for major studios to

whom he has brought, despite the constraint of efficiency, that little extra soul which is

lacking in so many of the local hacks. "I think that the Americans have a rather precise concept

of what the French or Latin composers are good at, they are usually looking for that romantic

vein, which we are famous for. This is why Georges Delerue, Morricone, Jarre and Legrand have

been so successful in Hollywood. In my case, it's probably more because I am not classifiable,

my taste for so many different styles has allowed me to have my own niche. African-Americans are,

for instance, very comfortable with me. They can identify with my sense of rhythm and my

grooves, (some of them have nicknamed me 'the funky Frenchman')."

Recently, Michel Colombier has written the music for the TV series Largo Winch, programmed

on M6, and, through it, has signed his great return in France. Temporarily, madam and the girls

will be back soon from shopping, and, the following Saturday, he will already be in his studio in

Los Angeles, where he will be a Frenchman in America with the same ease as he is an American in

Paris.

~ Christophe Conte

[back to Press] |